Inside OSCA

The Bolognese miracle that amazed the world

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

MAURO FANTUZZI’S MEMORIES – AN EXTRACT

My father had worked at Maserati, as had my uncle Medardo, the famous Fantuzzi coachbuilder. Already as a child, Ernesto Maserati had told me: “As soon as you’re old enough to start working, come to see me.” In fact, I was 14 when I turned up at OSCA in San Lazzaro one day in 1956.

The first job I did, together with Martino Avoni, was cleaning the factory windows, one of us working inside the building, the other outside. It was hard work because there was so much glass — it took a whole month.

Then they put me next to Giovanni Marè and everyone wished me luck. Marè was called ‘the cursed cripple’, since he was marked by God, but his head and hands were formidable. He was an extraordinary mechanic and rather bad-tempered, almost an artist if you want, even if he wasn’t very keen on teaching. I got callouses from using a scraper to give aluminium cylinder heads a smooth finish, because our engines didn’t have gaskets. I had to help slide the scraper by dipping it in milk.

At the time Ettore Maserati was restoring a machine to make spark plugs. Signor Ettore’s spark plugs were exceptional, especially because they could be disassembled and cleaned so they were as good as new again. He had been working on them since before the war, even though nobody ever fitted them. He was the only one to use them, on his Fiat 1100 TV convertible, and he never changed them, because he would just refurbish them when needed. All three Maserati brothers had, for at least a decade and maybe more, one of these little Fiat sports cars. The brown one belonged to Bindo, the grey one to Ettore and the blue one to Ernesto. And on all three they had rebuilt the engines to make them go faster. Of course, Ettore only wanted to use his own spark plugs on his car.

At OSCA, however, Lodge, Marchal and Marelli gave us spark plugs for free to use on our racing engines; we mainly used the Marelli 1001 and 1002, while Ferrari used the Marchal HF34. Also very good were the Lodge RL47 and RL49, which had the advantage of working well even with a cold engine. But this was Signor Ettore’s favourite area. He was a master when it came to electricity, wires and so on. At first it was difficult for me to understand what he was saying because he always used French terms for mechanical matters. For example, spark plugs were always bougies and he called the distributor a trembleur.

After that, I moved on to build engines. By that time there were 35 of us at San Lazzaro. I worked almost all of the time with Marè, who had his workbench next to Miccoli’s, and the two didn’t get along very well. There was often a battle between them as to who would finish his engine and then put it on the test bench first. Or to see who had found the most horsepower, with a subsequent discussion as to whether they had done the test correctly, because there could be a difference of 1.0–1.5bhp just from how the equipment was used. Initially, we only had one test bench, but after Fiat became involved, a second one arrived.

With completed cars, we mainly went testing on the road to Monterenzio, in the Idice valley, as far as Bisano. In the early days, we prepared about one racing car a month, then, when we reached an agreement with Zagato and Fissore, we also assembled two or three road cars, because the cars arrived with the bodywork already on them and we only had to fix the mechanical parts.

All three brothers were made a Cavaliere (Knight), while Ernesto was also honoured as a Commendatore (Commander). I always addressed Bindo by the title Cavaliere, but for me the other two brothers were always Signor Ernesto and Signor Ettore.

Mine was really a round-the-clock schedule, because between the hours I had to do in the test room and everything else, I would sometimes get home at six o’clock in the morning. Even Cavaliere Bindo discovered this on one occasion, after seeing me at the barber’s shop at ten o’clock one morning. He didn’t say anything at the time, but back at the company he checked my timecard and saw that I’d worked until the early hours that morning and had no reason to reproach me!

After the agreement with Fiat, the number of engines to be put together grew out of all proportion: they wanted more and more, because ours had 110bhp compared with the 95bhp of the similar engines they built themselves, due to the workmanship at Fiat being very sloppy. It wasn’t for nothing that we also had a workbench just for aligning crankshafts.

The pride of working at OSCA was enormous. I later had the opportunity to join both Alfa Romeo and Fiat, but it was entirely something else. At OSCA you never heard an employee speak ill of the company or the Maseratis in general: we all had great respect.

GRUMPY ERNESTO

How did the Maseratis treat us? Signor Ernesto was the most volatile and could lose his temper quite unexpectedly, especially with his brother Bindo. With us, however, he was always quite friendly as long as we worked hard, but I did see several workers who had displeased him thrown out on the spot. In particular, I remember the departure of Medardo Gubellini, who was in most respects very good but kept making the same mistake without asking for help. Signor Ernesto couldn’t accept that, because he was always available to teach, to explain; for him, if an employee wouldn’t recognise his mistakes, he couldn’t carry on under the same roof.

However, Signor Ernesto had a generous heart and was also quick to notice when something might be useful to the company. In Gubellini’s case, the man ended up going out through a door and coming back in through a window. At that time, machining crankshafts and camshafts on a lathe was really difficult, not like today when CNC machines do everything. So Gubellini set up a lathe inside a chicken coop at his home near Medicina, with chickens running around it, and supplied crankshafts to OSCA from outside. Yes, Signor Ernesto was always inclined to forgive. Many of the workers at OSCA called him ‘Il Leone’ (‘The Lion’), because he would snap suddenly, but then he would quickly get over it and almost regret being angry.

Sometimes he even lost his temper with me, although I was devoted to him and he appreciated me. One time it happened when I had to drive him to Cascina Costa [a journey of about 170 miles] to see Count Agusta of MV. I had to meet him at his house on the hill of Via Bellacosta but I arrived five minutes late because I’d under-estimated how long it would take to get there after having to go via San Lazzaro to pick up a car for us to take. He was always very punctual and that day he was in a bad mood too, so he told me off.

Then, after driving through Modena, we encountered such thick fog that I couldn’t see a thing and had to slow right down. Still cross about our late departure, he started swearing at me and angrily saying over and over again: “We can’t get there in time, we can’t get there in time...” So I replied: “Look, I can’t go any faster than this, I just can’t.”

I had already overtaken a dozen cars, spotting them in the gloom only thanks to their rear lights, which in those days were tiny and gave out very little light. The tension of driving like that wears you out after a while and eventually I had to have a rest. When, just after Parma, I drove into a layby at the side of the autostrada, he asked me what on earth I was doing and ordered me to continue. I answered with some bitterness: “Signor Ernesto, I can’t take it any more, I just don’t feel I can manage. We’re in danger of having an accident here.”

Just a few minutes later, while he was still moaning away at the top of his voice, we heard a huge crash of sheet metal screeching, bang, bang, bang, and then a car passed us within millimetres, out of control, before ending upside down in a field. Straight away, lots more cars smashed into each other and it seemed like the carnage would never end.

At that point, I wondered what had made me suddenly decide to stop the car at that very moment. I had no idea, but maybe someone from above had helped me. When it was all over, Signor Ernesto simply said: “I think we did well this time.”

Then, on the return journey, we were approaching the San Martino service area, a place with a reputation for good food. He told me to stop there, and said: “I’ll buy you dinner because I owe you an apology.”

THE MAER ENGINE

Signor Ernesto was always like a father to me and that’s why I also used to go to work at his house in Via Bellacosta during the evenings, since some engine design he did only at home, in his garage. In particular, there was the ‘Maer’, which stood for ‘Maserati Ernesto’, a revolutionary engine in many respects. It produced exceptional power in relation to its very small displacement, but it never went into production and is now on display at the Museum of Industrial Heritage in Bologna. Not surprisingly, it generated a lot of heat, so we tested it on the banks of the Idice river, using river water for cooling.

My only ‘remuneration’ was the pleasure of listening to his stories of the incredible era when he’d raced with big names like Tazio Nuvolari, Giuseppe Campari, Baconin Borzacchini, Achille Varzi and so on…. He used to make me laugh when he told of the time in Germany when the Maseratis finished first, second and third ahead of the Auto Unions, and, he said, “Benito masturbated next to Hitler in the grandstand.”

The Maserati brothers weren’t exactly on the same side as Il Duce, so much so that when they received from Mussolini himself a huge trophy, as tall as a small child, they kept it hidden out of sight in a basement.

Word also got around that when Mussolini himself had visited the Maserati company with all his hierarchy in tow, he arrived to find the brothers absent. Supposedly, according to the man assigned to welcome Il Duce in their absence, “The gentlemen have had to dash to the countryside because their father has fallen out of a tree and hurt himself.”

In short, Signor Ernesto was a legend for all of us, and not only because of his past as a great driver, but mostly because he was a superb technician. He was also very good at playing the piano, even though he was self-taught: I remember that some evenings, when I went to his house to work on an engine, I could hear him blasting out tunes at full volume when I arrived. That often meant he didn’t feel like getting down to work immediately.

TRIPS TO MV

When Signor Ernesto needed to go to MV’s headquarters in Cascina Costa in the Varese area, I always drove him there. He usually wanted to arrive around mid-morning and that meant a very early departure time, so the previous evening he’d say: “Mauro, pick me up at 6.30 tomorrow morning.”

On the outward journeys he was always cheerful, while on the return journeys he was usually downcast. It was like this because the Maserati brothers were proud people, and they had the right to be proud, but they clashed with the MV company and it didn’t work out well.

Count Agusta was an objectionable man, always rude, always made you wait in the reception area, even for hours, no matter who was meeting him. What’s more, he didn’t treat the Maserati brothers with the respect they deserved. Even his daughter couldn’t stand him, and once, when some of MV’s workers went on strike, I saw her on a picket line at the company’s entrance gate.

Signor Ernesto once sent me out to Portofino, where Count Agusta kept his personal yacht, to take him some documents: “You’re going because I don’t want to see him.”

Early in the morning I got into one of the test cars in the courtyard and set off with some concern, because I’d never been to Portofino and I wasn’t sure how long it would take to get there. The Count was supposed to be on board his yacht moored in the marina, but when I arrived, almost three-quarters of an hour early, I couldn’t see the boat, or at least I couldn’t see any boat with the name I’d been given. On the other hand, I noticed there were some empty berths, so I asked a man who seemed to be on duty at the harbour if he could tell me anything, and he replied: “Look, I know they’ve left, as he and his brother had to go somewhere.” So I asked if he had any idea when they would be back, since I had an appointment with them to deliver some papers, and the answer was literally: “You’re asking me? Those guys always do whatever they like when they set sail.”

I waited for more than an hour and eventually I headed back home. When I arrived in San Lazzaro, Signor Ernesto came up to me and wanted to know how it had gone. I explained to him that nobody had been there for me in Portofino and so I’d returned.

“And the letter you had to give him?”

“I brought it back with me. I couldn’t have trusted anyone else with it!”

“You’re crazy, it’s very important! Go back there now and make sure he gets it.”

As he ordered me to head back to Portofino again, he hurried to phone the Count’s secretary, but she had no idea where her boss might be either. So I got back on the road and waited in Portofino until evening, when the boat finally returned. At that point I introduced myself to the crew, but they wouldn’t let me aboard.

“Wait there on quay until the Count is available to come down and see you!”

This charade went back and forth a few times. Finally, the Count appeared and gave him the letter. And what did he say? Just, “Wait here.”

After another half hour, he handed me a little bag containing some papers, so finally I was able to go home. It must have been important stuff if it interested Signor Ernesto so much.

TEST DRIVING WITH ERNESTO

Unlike anyone else involved in test-driving the cars, Signor Ernesto preferred a route along the Val di Zena [a valley in the mountains south of Bologna], taking a road that began right in front of the factory. He enjoyed driving there because the road was a rewarding one for a driver, with sequences of bends, and never too tight. Everyone else did their test drives on a different route southwards, to the town of Monterenzio.

I often used to go with him. This testing was done before a car had its bodywork, so there was just the chassis, the engine, the transmission and the two seats. Of course, we were totally exposed to the elements — and of course Signor Ernesto, a true racing ace in his time, would drive really quickly to put the car through its paces. We would go out regardless of the weather, so I would consider myself lucky if it wasn’t raining and wasn’t too cold. If it was, I would be soaked through and shivering in no time.

TEST DRIVING WITH BINDO

Of course, I also tested cars myself, and used to take that ‘official’ route up to Monterenzio. Sometimes when Cavaliere Bindo heard me starting a car to go and try it out, he would appear out of his office wearing his cap backwards. I always knew what that meant: he was going to come with me! Because we tested the cars before they had their bodywork fitted, that was how he would prevent his cap flying off. We would invariably have a little debate, because he usually wanted to take a different route.

“Where are you going?” he would ask.

And I would reply: “As usual, I’m heading towards Monterenzio.”

“No come on, listen to me, let’s go to Modena.”

The reason was that in Nonantola, a small town near Modena, there was someone who produced very special salamis, top quality and really delicious. He just adored those salamis. So I had to drive all the way to Nonantola, to Candi’s, to buy the usual salamis, and also he liked to get balsamic vinegar there.

One time Bindo said he wanted to drive back from Nonantola. That meant going towards Modena and around the outskirts of the city to get on the main road back to Bologna. When we got close to Modena, I realised that he was driving straight towards the city centre and I thought to myself, “We’re going to get stopped and fined.” The car wasn’t entirely road-legal but that didn’t matter out in the countryside.

Actually, he had a reason for driving into the city. At one point he said, “See that window?” I nodded. The shutters were closed and it looked like nothing at all. He started laughing, as he used to do, in his slightly husky way, and said: “That’s where I used to come for a good shag!” I wondered to myself why it was really necessary to come into Modena just for that, but it was obviously a special memory for him. In such moments together he was great fun. Bindo was the most playful of the three.

The only problem was that Signor Ernesto didn’t like his brother going off with me like this because he knew only too well that Cavaliere Bindo would want to drive. Bindo was a lot older than his brothers and by this time he was in his 80s, and thought to be not entirely safe driving a high-performance OSCA with no bodywork! But actually when Bindo had a steering wheel in his hands, the years seemed to melt away and he drove well — and very quickly.

One time with Bindo we were going towards Monterenzio, on our usual test route on this occasion, and he was driving. Coming into the village of Castel dei Britti, he lost control of the car and hit some tables and chairs outside Deborah’s bar, an establishment owned by a woman nicknamed ‘the brunette’ because she had so much hair of that colour.

“Check if we’ve done any damage,” Bindo asked. I joked back, “We’ve definitely done the car some harm, and we’ll learn about trouble at the bar when we get back to San Lazzaro!”

This was a sports car with bodywork and it wasn’t exactly in great shape after the incident, especially at the back. However, Signor Ernesto never said anything to me about it even though he’d told me not to let Bindo drive. But I was an employee and Cavaliere Bindo was one of my bosses: how could I tell him that?

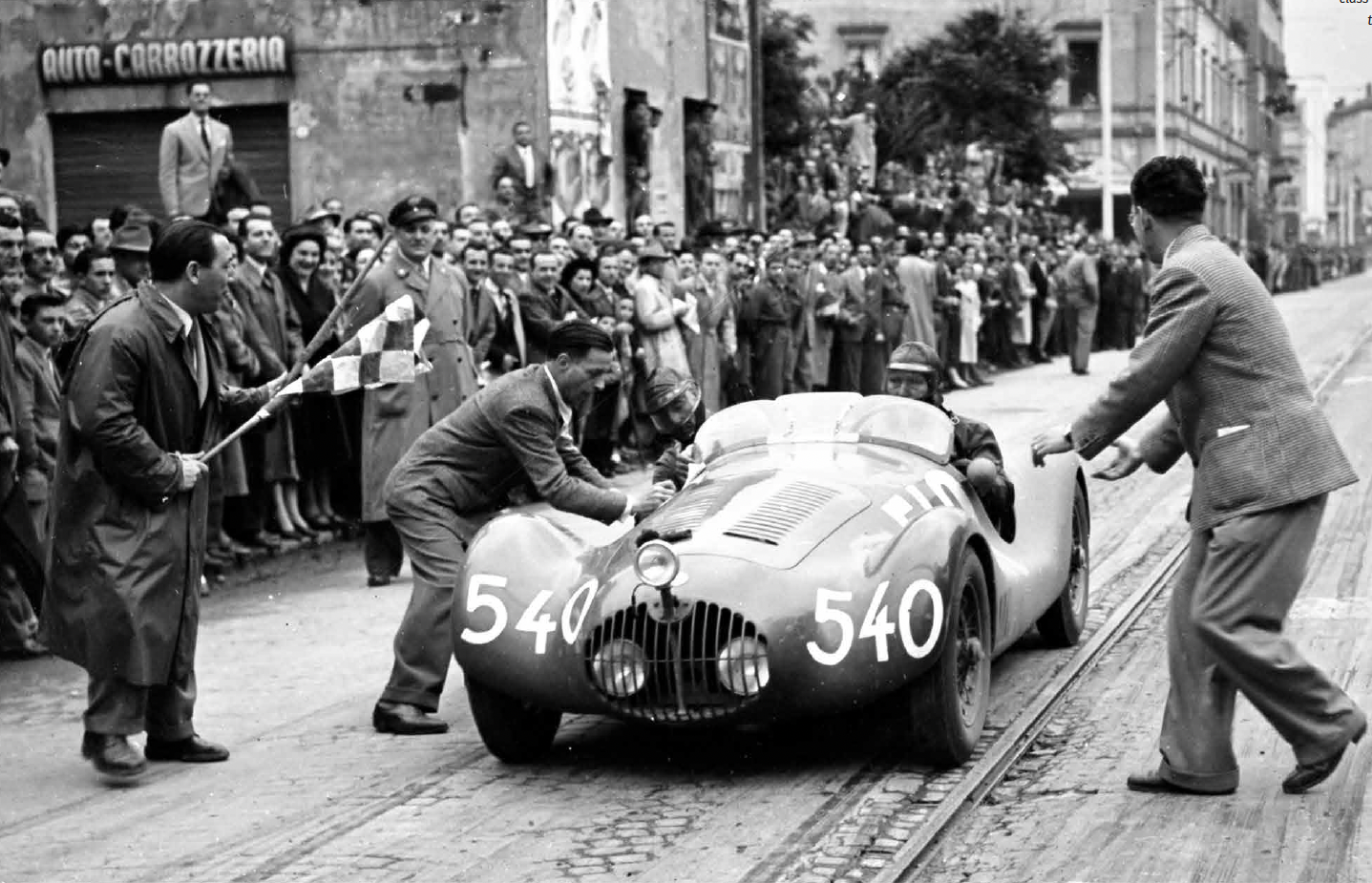

• The 225 photographs by Walter Breveglieri are mostly reproduced at generous size and capture so much wonderful atmosphere, whether in and around the factory or on the track, with street races of the 1950s featuring strongly.

• Because Breveglieri lived near the OSCA factory, he could often drop by and photograph precious moments, such as a visit from Prince Bira or a test by Louis Chiron on nearby public roads.

• Long-time employee Mauro Fantuzzi is a focus of the book with his numerous colourful memories of the people and the cars, including insights into the talents and characters of the three Maserati brothers.

• Two other employees, Martino Avoni and Luciano Rizzoli, share recollections, including stories about drivers such as Juan Manuel Fangio, Alfonso de Portago, Ricardo Rodriguez and Ludovico Scarfiotti.

• Before their deaths, Stirling Moss, who raced his own OSCA in historic events, and Maria Teresa de Filippis provided the author with their reminiscences.

• OSCA’s road cars also feature, with bodies by coachbuilders such as Zagato, Vignale and Fissore.

Format: 280x240mm

Hardback

Page extent: 272

Illustration: 225 black-and-white photos

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.