For Flux Sake

Beer, fags and opposite-lock

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

Chapter 4

Graham Hill: learning from the master

With the Token Formula 1 team, I’d glimpsed a life that I really wanted but it had been snatched away. Just before Token closed, however, Neil Trundle phoned the workshop. Ray Jessop’s wife answered the phone and said he wanted to speak to me. Neil said he’d heard that Token was shutting. He said he would call Graham Hill’s Formula 1 team on my behalf because he knew they were looking for a new van driver.

Neil put in a good word for me. I didn’t even have to go for an interview. Neil just rang back and told me I would be starting at Embassy Hill the following Monday. The team was based in Feltham, in the old Rondel Racing workshops, as Graham had raced for Ron Dennis’s team and then taken over the premises after Rondel’s closure. Graham had set up the team in 1973, running a Shadow, then turned to Lola in 1974. Now he was starting to build his own car, the Lola-derived Hill GH1.

Ray Brimble was the team manager. When I arrived on the Monday morning, he took me upstairs to introduce himself properly and told me I was there for one month’s trial. My first task was to fill the team’s Ford Transit with fuel and go to Earls Barton near Northampton where John Thompson’s company TC Prototypes built the monocoque for the GH1.

Embassy Hill was a much bigger set-up than Token. It was a proper team. I think there were 19 of us rather than just the four we’d had at Token. Andy Smallman was in the drawing office upstairs, Alan Howell was on the engineering strength and Alan Turner was the chief mechanic. There was even a secretary.

When I went to Token in 1974, I was on £25 a week, but at Embassy Hill I stepped up to £30, so I knew I’d really made it in grand prix racing at that point.

The first time I went anywhere with the team was a test session with Graham at Goodwood. Three of us went down there and my job was to hang out the lapboard. Graham was sponsored by Firestone and used to get paid so much per mile, so his idea of a day’s testing was to do as many laps as he possibly could — ker-ching! I think he was doing times around 1m 7s, something like that, and I was hanging them out every lap: ‘7.1s’, ‘7.2s’, ‘7.1s’. He just seemed to drive past without looking at my board so I began to feel like I was standing there for no good reason. I asked the other two if he ever actually took any notice of the times. They said they didn’t think he did and suggested we should have a bit of a laugh.

In those days, you had loose letters and numbers that you attached to the board. They wanted to put a very rude word beginning with ‘C’ on the board for one lap but they didn’t have a ‘C’. So I hung out ‘Gunt’. On the very next lap, Graham came in: “What the fuck was on that pit board?” We told him it was the lap time, but he knew it wasn’t. I was standing there all innocently and he called me over. He said, “It’s a good job I have a sense of humour… However, this is the first time I have ever met you and I don’t expect to be called a ‘Gunt’ on my first acquaintance with a spotty 18-year-old.”

The atmosphere in the team was always slightly different when Graham was present. A hush would go around the workshop: “Oh gosh, Graham’s here.” The Old Man — that’s what we used to call him — could be hard work. Because I was just the dogsbody, it didn’t really affect me, but the mechanics were wary of him.

We used to have a lot of meetings, and one time I remember him laying down the law to everyone. He pointed at me and said, “If Fluxie doesn’t go and get the parts, you mechanics haven’t got the parts on the car to fix — it is a team.” I remember him picking me out in this meeting. It stuck with me, what Graham said, but at the time I just remember being delighted that he knew my name.

Anyway, at the end of the month’s trial, Embassy Hill kept me on over the winter, and we worked harder than ever, flat out building the first brand-new Hill GH1 for the 1975 season. I think I only had Christmas Day and Boxing Day off.

One day Ray Brimble told me to go and pick up Graham from his solicitor’s office in Soho and take him to Gatwick Airport. The solicitor was called Lewis Cutner and ten years later he got struck off for being bent. I asked Ray which car he wanted me to use and he just pointed at the Transit and said, “Take that.” I said, “Are you sure?” I found Cutner’s office down this narrow street in Soho. It was hard to park anywhere. I turned up at the door wearing my Embassy jacket. I told the secretary to let Graham know I was there and then returned to the van because I was worried I might have to move it. Graham came out, I shook his hand and he got into the van.

There we were, chatting away. I don’t know why, but by this time I’d had some successes in my racing career and I was much more confident. Graham said, “I hear you do a bit of racing?” I told him that I competed in Formula Vee and said it was going well but I had yet to win a race. Then something clicked in me. I thought, “It’s Hyde Park Corner, it’s a bit damp and slippery — now’s the time to show the boss what I can really do.” I was yanking this old Transit around. It wasn’t properly sideways, but I got it a bit out of shape.

I remember passing a taxi and seeing Graham wave out of the window to the cabbie. He had to do that because there was nowhere for him to hide: we were in a van with ‘Graham Hill Racing Team’ emblazoned down the side. He was not amused. He said something along the lines of, “I have a flight to catch and I don’t want to be ill getting onto the plane.”

I delivered him safely to Gatwick but as soon I got back to work, all the others were pointing at me and saying, “You’re in trouble!” I had to go up to Ray’s office and he said, “You’ve caused yourself some shit. I have had the Old Man on the phone and he wants me to sack you.” I couldn’t understand why. Then Ray added, “Mr Hill thought you drove like a complete lunatic.” I apologised.

Ray explained to Graham that just two days before I’d driven all through the night on a great big round trip to Lola in Huntingdon, TC Prototypes in Earls Barton, Cosworth in Northampton and BS Fabrications in Luton, and that I was an asset. Ray said, “I persuaded him to keep you but there’s one condition: he never ever wants to be driven by you again.” And he wasn’t…

My appetite for a party was still strong, but with my new employer there was no way I could get away with things like I had done at Token. It was a bit more serious. The first time I went away with Embassy Hill was the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch in March 1975. It was also the first time I had happened across the Embassy promotional girls. We were all staying in the same hotel somewhere on the A2. We were all there in the evening, including ten of these girls, and nobody seemed to be going to bed — and I wasn’t going to suggest it. It was very much work hard, play hard in those days.

The next race I attended was the French Grand Prix. By this time Graham had retired from driving — he stopped after failing to qualify in Monaco — and I was needed at Paul Ricard because this was the first time the team was truly at full strength, with two GH1s for Tony Brise and Alan Jones plus a third as a proper T-car. My main job was to deal with the fuel, keeping all three cars filled and emptied as necessary. I did the trip in the transporter and made sure the cars were topped up for the return journey so that we could siphon out the fuel when we got back and share it around the mechanics. Thank you, Esso.

My only other race with Embassy Hill was the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, where my duties were the same. Graham got back in the cockpit there and did one lap in the T-car, waving to the crowd all the way round. Ray Brimble wanted me to go to the Osterreichring and Monza but they clashed with Formula Vee races and I’d said from the outset that my own racing would have to take priority.

I remember Tony Brise joining the team after Graham stopped. He had to come to Feltham for a seat fitting. He was due at 10am but it was 12.30 by the time he eventually turned up and he didn’t really apologise for being so late. Anyway, we got on with the seat fitting, which involved putting two-part foam in a dustbin bag, sitting Tony stock still on it for half an hour, and letting the foam set around him to exactly the right shape. After that, you had to cut away the solidified foam that had spilled out around him so he could escape. But because Tony had been a bit of a prima donna and the job had gone into our lunch break, we just buggered off anyway and left him there for an hour.

Alan Jones had four races with us, starting at the French Grand Prix. What I remember most was his incredibly attractive wife. Bev was so easy to talk to and I adored being with her. I had some very pleasant dreams about her for a while.

Graham was always very closely involved with the team. We used to see him whenever the truck came back from a race weekend and he would still be there after it had been unloaded, talking to us all about what had to be done. Then he would be out and about much of the time finding the funds but would usually be around when the truck was ready to leave for the next event. He was the backbone of the whole thing.

I was in awe of Graham, I really was. When I met Tom Pryce, he was a hero, but he was much younger, very laid back and had come up through the ranks like I was trying to do, so I felt a bit like him to a very small degree. But Graham had been a star for a long time. I would have seen him race at my very first meeting at Goodwood, when I was five, even though I couldn’t remember it. Hill was a double World Champion and a BBC Sports Personality of the Year — a real celebrity.

On one occasion while I was working at Graham’s, I got home to find police waiting for me in the front room. I wondered what was up. I thought one of the neighbours must have complained about my driving — again. The coppers asked me if I knew a guy called Les Porter. I said “yes” and told them he had taken me kart racing when I was 13. They asked if anything untoward had happened and I said “no”. I couldn’t bring myself to say anything about what had really gone on. Mum and dad were there, and I just didn’t want to jeopardise anything. I didn’t want to get involved.

I had a great job with Graham Hill. My own racing was going well and I was leading the Formula Vee Championship. Why would I want to put any of that on the line for this man? I thought, “Why do I need to bring anything up? He has obviously been caught.” He’d been arrested after another boy complained to his parents. I thought that saying something wasn’t going to bring me any benefit and anyway he was going to go to prison regardless. He did eventually serve time — so both of the men who had assaulted me ended up being jailed.

After I won my third Formula Vee race on the trot during that 1975 season, it suddenly struck me that this was something I could do for a living. It went from being fun to being something I seriously considered. Before that, I’d been quite happy doing my Formula 1 job, but it got to the point where I could do my own race driving almost without thinking. Everything I raced, I just got into it and won. But I still loved my job in Formula 1.

At the end of the season, after I’d won the Formula Vee Championship, all the Embassy Hill boys came down to watch me in the last race at Brands Hatch. I remember talking to the circuit commentator, Brian Jones, on the rostrum after the race and there were a load of Hill mechanics all there cheering. They were all there for me and they were all shaking my dad’s hand and congratulating him on preparing the car.

When Graham found out that I’d taken the title, he asked if I would like a pair of his old overalls. I thought that was a lovely touch. They were silky-type Gold Leaf Team Lotus ones. I never used them because it didn’t seem right and anyway I was getting free overalls from a supplier. I kept them for over 20 years and then put them in a Brooks auction and got £9,500. That paid for an extension to my house. We always called it the Graham Hill wing.

Tragedy struck at the end of the season, on Saturday 29th November, when Graham was killed along with five members of the team — Tony Brise, Ray Brimble, Andy Smallman and mechanics Tony Alcock and Terry Richards — when flying back from a test at Paul Ricard in the South of France.

I was never going to be at that test. We were still trying to build one of the new cars for 1976, the GH2, so I was at the workshop. This was the second of two test sessions at Paul Ricard and the first hadn’t gone well because the first GH2 was rubbish out of the box. This second test went better and I remember we received a telex in the office that Friday afternoon to say they had put the rear end of the original GH1 onto the tub of the GH2 and all of a sudden it went two seconds a lap faster. It was all looking good and the mood was upbeat. They said they were calling an end to the test and coming home early.

On the Saturday night, I went to see the band Queen at Guildford Technical College. Because bands were often booked well in advance, Queen had been lined up for this gig before they were famous. They rocked the place. That evening I met a girl called Carol Ives during the half-time interval. I convinced her I could run her back to her home in Cranleigh, just down the road, because that’s where my gran lived.

There was a thick fog, extremely bad that night. It was a proper pea-souper and I was driving very slowly and carefully, making sure I got my precious cargo, my new best friend, to her home. We had Radio Luxembourg on in the car. The normal news bulletin came on at 11.00. It said there had been a light aircraft crash at Elstree aerodrome — and I just knew. I knew the team was meant to be coming home that evening and my heart sank to the pit of my stomach. I panicked a bit.

I got Carol to her home. I explained to her that I thought the news report was probably about people from work and they were potentially my friends who’d been involved. I asked her if I could come inside and use her parents’ phone. I rang ‘Moby’, Alan Turner, the chief mechanic, who hadn’t gone to the test. He confirmed the worst and I asked if I could come round to his place. As I got there, at about midnight, he was getting in his car and about to drive off. He had to go and identify the bodies. He told me to go into his house and wait with his wife. When he came back, he said they were so badly burned that he could only identify them by their watches.

The plane crash was a seismic thing and so unnecessary. As it turned out, Graham’s plane wasn’t insured and it had the wrong altimeter, but besides all that, if only he had flown to Luton, as he had been told to do by Air Traffic Control, instead of chancing it at Elstree in the fog, then none of it would have happened.

But that was Graham. His outlook to anything was, “I’m doing it my way”. His road car was at Elstree and he had a dinner party to go to that evening and I think he just didn’t want the hassle of landing at Luton and not having his motor with him. He took risks, but this one had such a dreadful outcome.

It didn’t put me off motorsport because it was just someone not doing what he was told. I actually felt far more affected when Tom Pryce died in the South African Grand Prix in 1977 because he was someone I knew as a racer. Tom couldn’t avoid a marshal running across the track with a fire extinguisher and it hit his head and killed him. He had been in a racing car doing nothing wrong but the result was the same.

Alan Turner carried on at the team to sell all the assets and I stayed with him because I was the cheapest member of staff, so there were just the two of us. It took us about three months to effectively close the place down. We became quite friendly during that sad period.

• Early days: growing up on a farm, first kart aged 6, muddling through in the classroom, lots of laughs — but also sexual abuse from a schoolmaster and an early racing mentor.

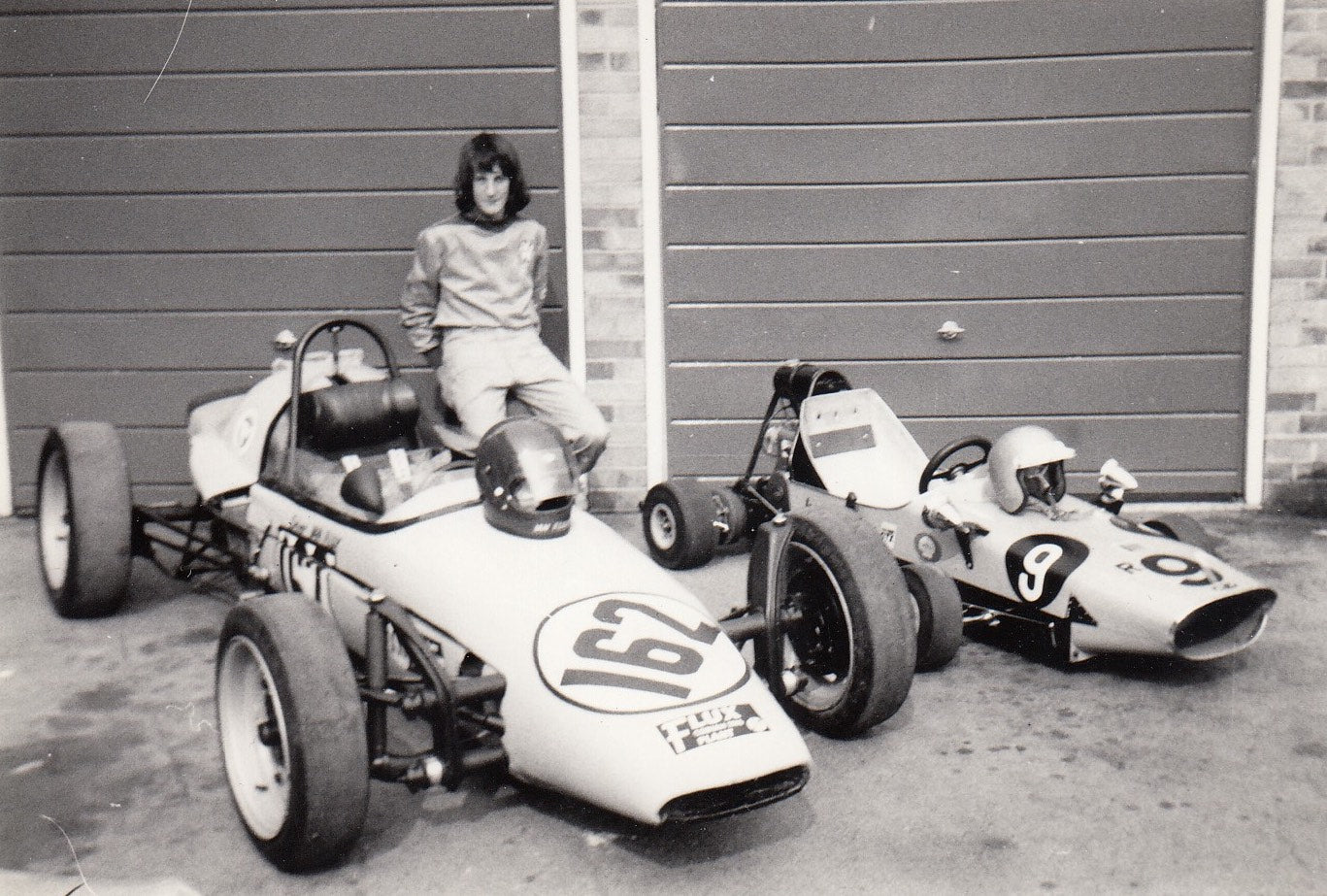

• The spark ignites: starting to race in 1970 with a Formula 6 kart, then onwards to Formula Vee; brushing shoulders with Formula 1 working for the Token and Graham Hill teams.

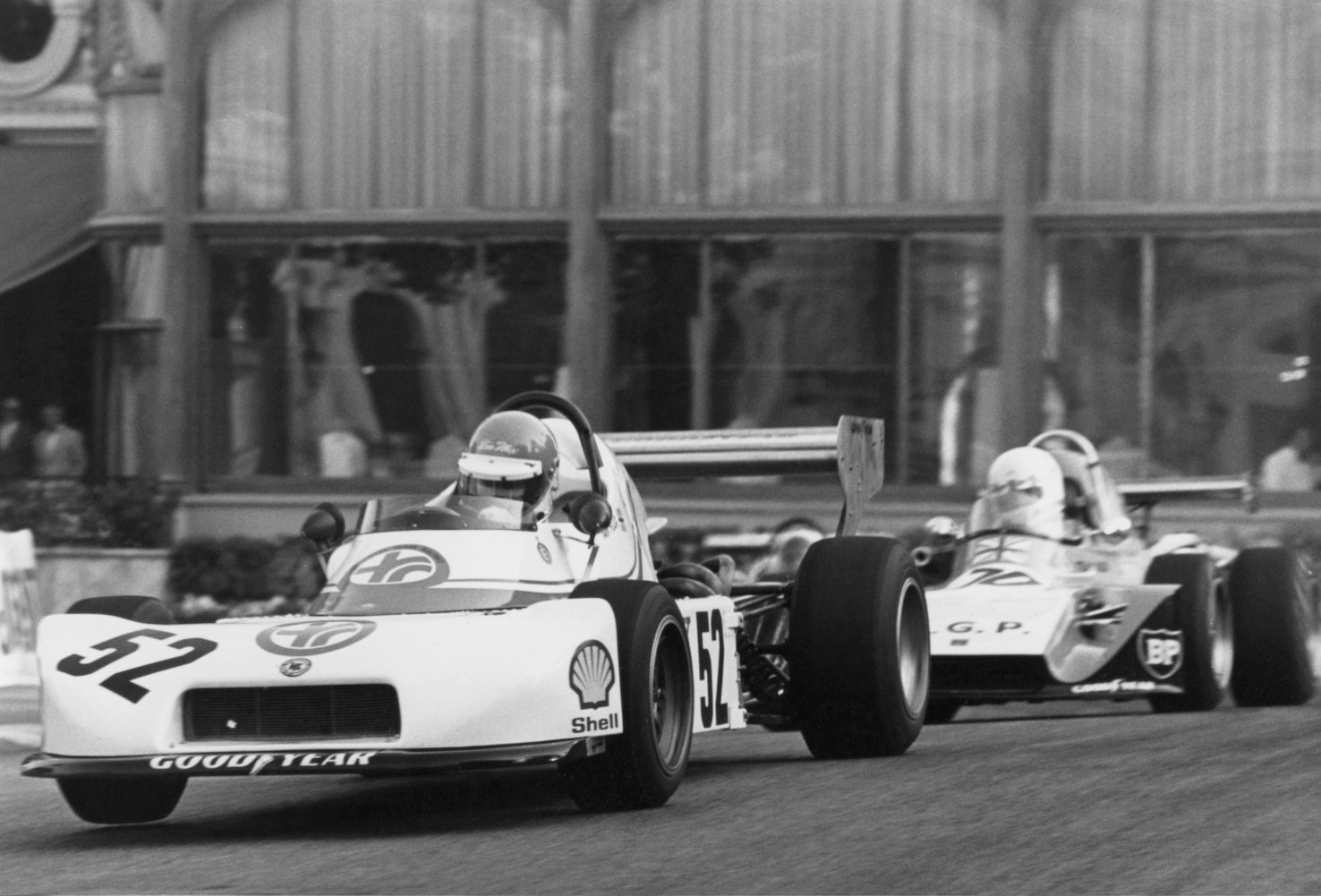

• Grabbing the chances: a Formula Vee title in 1975 leads to Formula 3 and Formula Atlantic, but still with various jobs to make ends meet, including as mechanic to motorcycle racing legend Giacomo Agostini for his four-wheel efforts.

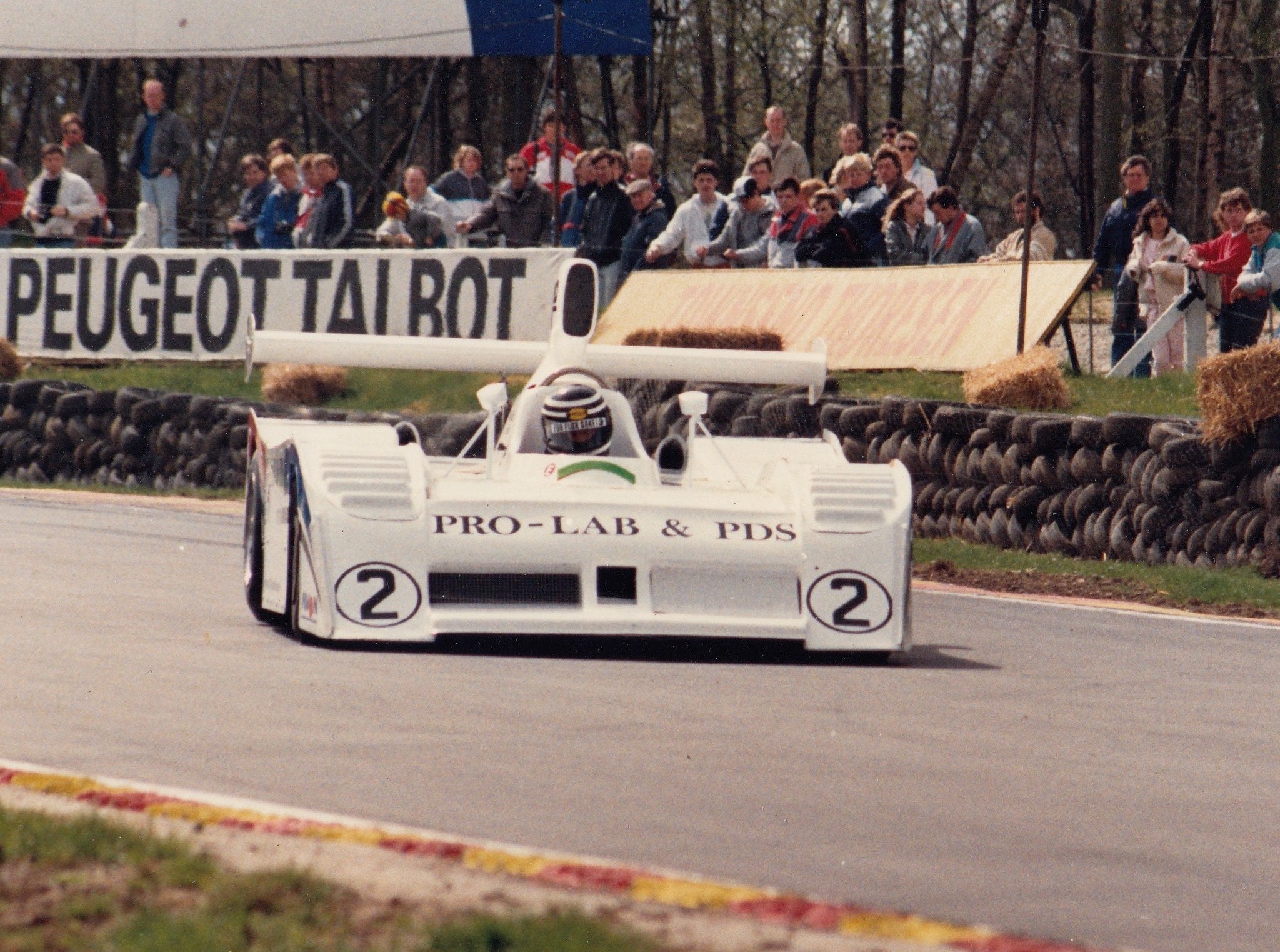

• Diversifying into sports cars: successful adventures in Sports 2000 and Thundersports, winning championships in both, plus Thundersaloons.

• A true all-rounder: going into the British Touring Car Championship from 1988 in a wide range of tin-tops; racing a Jaguar XJR-15 in the big-money 1991 series held at Grand Prix races, including Monaco.

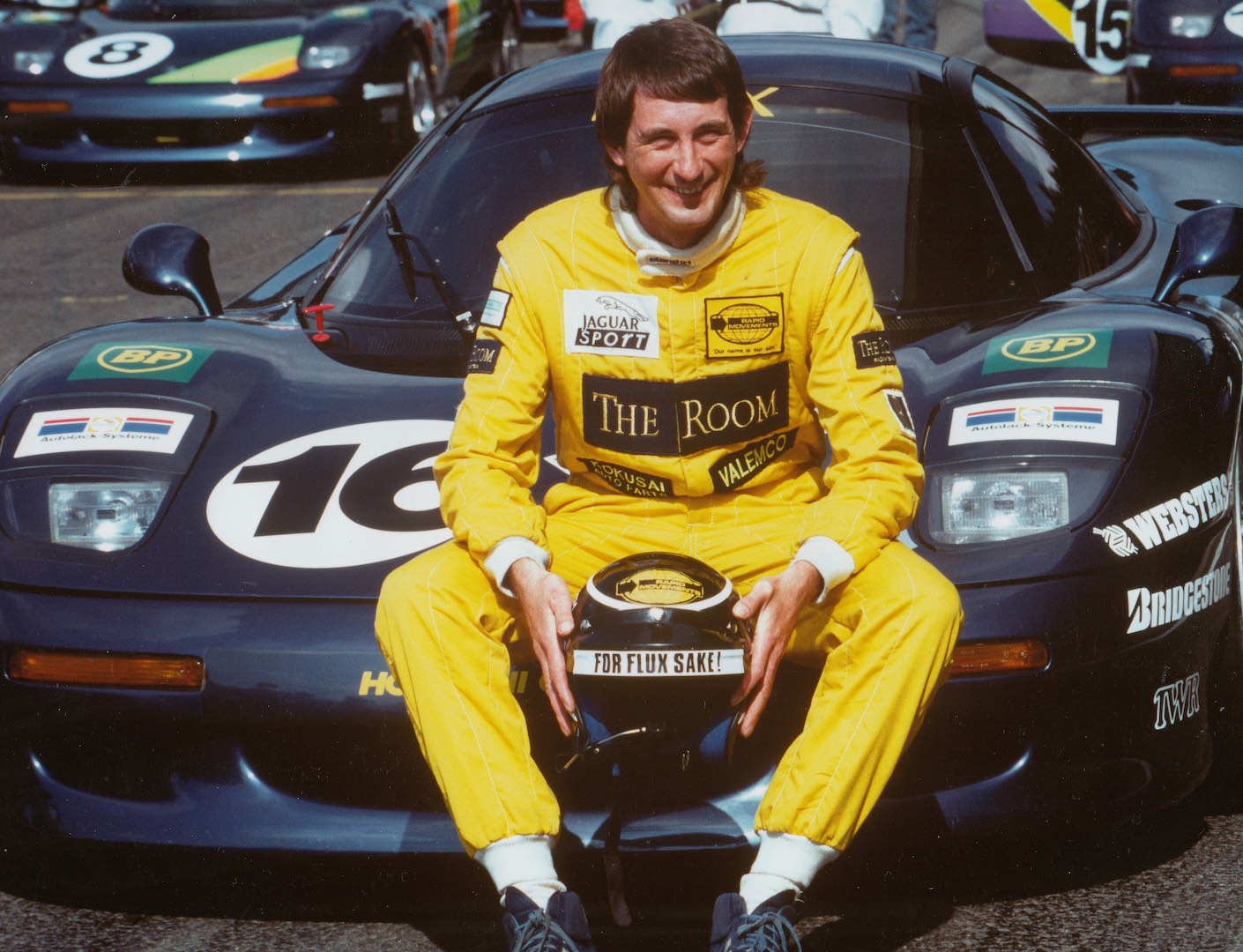

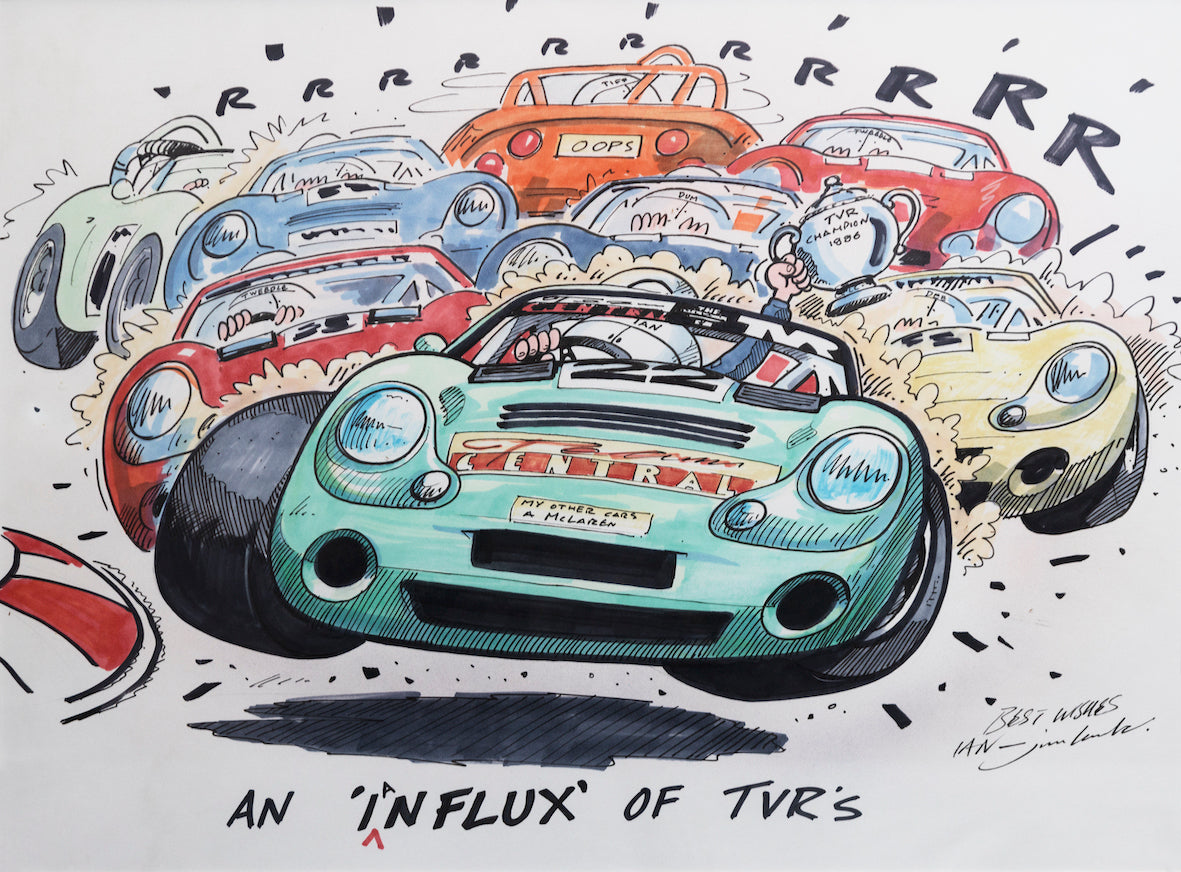

• Championship double in 1996: the ‘golden year’ in the TVR Tuscan Challenge and the British GT Championship, the latter with a McLaren F1 GTR.

• So much else: racing on into recent times, notching up nearly 50 years on track; testing competition cars for Motorsport News; driver tuition and track-day demonstrations.

Format: 234x156mm

Hardback

Page extent: 304

Illustration: 80 photographs

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.