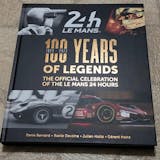

100 YEARS OF LEGENDS

THE OFFICIAL CELEBRATION OF THE LE MANS 24 HOURS

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

INCREDIBLE BUT TRUE

A sprint back to the pits

1923

During the inaugural Le Mans 24 Hours, the Bentley shared by John Duff and Frank Clement was challenging for top honours when it coasted to a halt in the early hours of the morning after a stone punctured its fuel tank. Duff, who was driving, knew that to retain any chance of completing the distance, he would have to run the three miles (5km) back to the pits and get his co-driver’s help. Using a bicycle borrowed from the police, Clement returned to the car with a five-litre (one-gallon) can on each shoulder, and plugged the breach in the tank with hemp thread and black soap. The British pair completed the race in fourth place, setting the lap record at 9m 39s, an average speed of 66.691mph (107.328km/h).

Escape from hospital

1927

One of the strangest episodes in Le Mans history occurred in 1927. Tracta entered two of its innovative cars, which featured front-wheel drive and very low build, but all four of the assigned drivers found themselves in hospital on Saturday morning after suffering injuries in a road accident on their way to the circuit. Nevertheless, Tracta co-designer Jean-Albert Grégoire was determined that at least one of his entries would make the start, so he escaped through a window while the nurses weren’t looking and took a taxi to the track. Despite severe bruising and with his head bandaged, his intention was to drive in the race — but he needed a co-driver and sought help from race director Charles Faroux. After a request over the public-address system for someone with a racing licence to step forward, Lucien Lemesle presented himself. The Tracta achieved its target distance and reached the finish, with Grégoire doing the lion’s share of the driving — an astonishing achievement.

Double trouble

1928

Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin, at the wheel of one of the 4½-litre Bentleys, was just finishing his stint at 7pm when he had a tyre blow-out on the Hunaudières straight. He managed to bring the big car safely to rest but part of the flailing rear tyre had wrapped itself around the hub and brake drum. Using a knife, file and pliers carried on the car, he spent 90 minutes cutting away the tangled rubber. With the wheel freed, he decided to drive to the pits rather than lose more time attempting to jack up the car and fit the spare wheel, a tricky task on the soft grass verge. He drove with the bare rim on the verge wherever possible but when he reached Arnage the wheel collapsed. Unable to replace it, he had no option but to run back to the pits and get co-driver Jean Chassagne to go out to the car with a hydraulic jack concealed about his person. Eventually, after a total delay of three hours, the Bentley returned to the fray and finished fifth, 19 laps behind the winning sister car of Woolf Barnato and Bernard Rubin.

Jumping out at speed

1930

The 5.3-litre Stutz Model M driven by Édouard Brisson and Louis Rigal gave trouble when the exhaust system came adrift. After a makeshift repair in the pits, Rigal set off at dusk and was hammering down the Hunaudières straight when part of the exhaust fell off, allowing flames spitting from the broken pipe to set the car on fire. In danger of getting consumed by the flames, he leaped to safety, landing on the track. Woolf Barnato in his Bentley miraculously avoided running over the Frenchman, who survived to tell the tale.

Chewing-gum repair

1933

Raymond Sommer and Tazio Nuvolari scored a fine win for Alfa Romeo in 1933, beating the sister 8C of Luigi Chinetti/Philippe de Gunzburg by just 401 metres (439 yards) despite a variety of problems along the way: a loose wing, faulty shock absorbers, brake trouble... and a fuel tank with a leak that progressively worsened in the closing stages of the race. As repairs could only be carried out using on-board equipment, this presented a challenge. The answer was chewing gum. Between pitstops, all the team members chewed away furiously to provide a generous supply of gum, nicely softened, to help plug the leak — and allow the star drivers to claim a glorious victory.

Solo driving

1950

Frenchman Louis Rosier won the race in 1950 after driving all but two laps in his 4.5-litre Talbot-Lago. He chose his son Jean-Louis as his co-driver but only let the inexperienced 25-year-old take over the car briefly following a 41-minute pitstop at 5am to replace a broken valve rocker arm in the engine. After mucking in with the repairs, Rosier Sr used his two laps of rest to freshen up and eat some bananas before getting back in the cockpit and attempting to claw back lost time. Rejoining third, he was back in the lead by 9am – and cruised on to win by more than a lap. He had driven for 23 hours and 10 minutes. In the same race, Eddie Hall uniquely drove the entire distance on his own, bringing his Bentley home in eighth place. Two similar displays of stamina occurred in this period, when there was no limit on driving time. In 1949, Luigi Chinetti, also with doubts about the talents of his co-driver, Lord Selsdon, took his third Le Mans win after driving their Ferrari 166 MM for 22 hours 48 minutes. In 1952, ‘Pierre Levegh’ mounted his own solo challenge in a Talbot-Lago but was cruelly denied victory when his engine broke after 22 hours and 50 minutes.

Key on the left

1951

The ignition key on a left-hand-drive Porsche is positioned to the left of the steering wheel, unlike on most cars. The origin of this unusual layout lies in the echelon start of the Le Mans 24 Hours. When the drivers had to run to their cars, jump in, start their engines, select first gear and pull away, Porsche judged that it would be just a little quicker to have the ignition on the left so that a gear could be selected at the same time as starting the engine. But is this an apocryphal story? The Porsche Museum in Stuttgart provides a different explanation, namely that the left-hand location used less wiring on Porsches of the time.

Struck by a bird

1953

During his first stint at the wheel in the 1953 Le Mans 24 Hours, Duncan Hamilton was belting down the Hunaudières straight in his Jaguar C-type, complete with pioneering disc brakes, when it struck a bird. The impact smashed the windscreen and the British driver suffered a broken nose, but he nevertheless persevered to complete his allotted time at the wheel, tilting his head to the left to avoid the blast of air. After repairs at the next pitstop, Hamilton and co-driver Tony Rolt raced on, took the lead during the night, and won by four laps. They almost didn’t take part at all. Jaguar had slipped up during practice by briefly allowing two cars with the same #18 — the regular car of that number and the spare — to circulate at the same time. This contravened the rules, which meant a fine and possibly even disqualification, but only a financial penalty was imposed. A great raconteur, Hamilton embellished the story in later years by claiming that he and Rolt drowned their sorrows in a Le Mans city bar on Friday night and only found out the following morning that they could race after all… with severe hangovers…

The long push

1957

During the 1957 race, Roger Masson’s Climax-engined Lotus XI ran out of petrol at the end of the Hunaudières straight. Rather than give up, Masson decided he would attempt to push the car to the pits, a distance of nearly four miles (7km). Admittedly, the Lotus was very light, just 1,050lb (480kg), but the weather was hot and it was an arduous task. After 90 minutes, Masson finally arrived, shirtless, and collapsed with exhaustion. André Héchard, his co-driver and the car’s owner, resumed with a full tank – and the pair went on to finish a creditable 16th.

Secret extra driver

1965

Ed Hugus, an experienced American sports car driver, had already raced in the Le Mans 24 Hours nine times — with five top-ten finishes — when Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing Team (NART) named him as a reserve driver for the 1965 event. According to the ACO’s records, NART never actually required Hugus to drive that year, but a few decades later he claimed, astonishingly, that he had been part of the winning crew. Shortly before dawn, stated Hugus, bespectacled Masten Gregory was at the wheel of NART’s Ferrari 275 LM when, exhausted and struggling with his vision in the misty conditions, he made a premature pitstop. Gregory’s young team-mate, Jochen Rindt, was nowhere to be found, so Chinetti asked Hugus to step in for a stint. And so it was that the American, flying under the ACO’s radar, secretly contributed to the surprise victory that Rindt and Gregory achieved come 4pm. This tale only came out when Hugus, by all accounts a modest man, happened to mention it when asked about the race. But historians remain divided about whether this is truth or myth. Now that those involved are no longer with us, we shall never know.

Attempted dead heat

1966

The all-conquering 7-litre Fords of Ken Miles/Denny Hulme and Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon completed the 1966 race almost neck and neck after Ford’s racing director, Leo Beebe, keen to obtain maximum publicity for his company’s first Le Mans victory, and with Henry Ford II in attendance, decided to try to stage a dead heat. With about an hour to go, Hulme, the leader, was ordered to ease off and let second-placed Amon get on his tail. Meanwhile, the ACO considered Beebe’s plan and told him that a dead heat on the track wouldn’t apply in reality because the outcome would be decided on distance covered. If the two Fords crossed the line side by side, the McLaren/Amon car would be declared the winner because it had started about 20 metres behind the Miles/Hulme car. Beebe, however, didn’t care who won — the spectacle of Ford’s greatest racing triumph in its history trumped everything. As the final laps unwound, Miles and McLaren were driving their respective cars, holding station in light rain with Miles rightfully ahead but aware that a dead heat would cost him and Hulme their deserved victory. Last time around, Miles, now angry about the fact that he was about to be denied victory, honoured the team’s wishes, but made his point as the two cars approached race director Jacques Loste with the chequered flag by lifting at the last moment, putting the McLaren/Amon car a length or two in front.

Champagne!

1967

Did you know that the ritual of champagne spraying practised by drivers the world over originated at the Le Mans 24 Hours? It all began with an amusing incident on the podium in 1966, when the organisers forgot to chill the champagne for the winning drivers in the 2-litre prototype category, Jo Siffert and Colin Davis in their Porsche 906. When the cork popped out unexpectedly, foaming champagne splashed people nearby. The following year, when Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt took a second successive overall win for Ford, Gurney remembered that incident and decided to give his bottle a vigorous shake. Everyone in the vicinity, including Mr and Mrs Henry Ford II and team boss Carroll Shelby, got a soaking.

Broken windscreen wiper

1968

French hopes in 1968 included Matra’s singleton entry of a long-tail MS630 with a new 3-litre V12 engine for Henri Pescarolo and Johnny Servoz-Gavin. The race started on a damp track after a heavy shower and Servoz-Gavin pitted at the end of the first lap with a windscreen-wiper malfunction. Thereafter, the car ran well and reached second place soon after nightfall. Then it rained again and still the wiper wouldn’t work, so ‘Servoz’ stopped at the pits, complaining that the impaired vision made it impossible to drive in darkness. As the wiper motor was inaccessible and difficult to replace, Matra’s boss, Jean-Luc Lagardère, decided to retire the car. Lagardère felt he should tell Pescarolo right away and woke him. Furious, ‘Pesca’ jumped out of his bunk, stormed off to the car and roared into the night. After his first flying lap, the team called him back in to make sure he could see properly — which made him even angrier. By dawn, he’d got back to second place. Sadly, with less than three hours to go, ‘Pesca’ was at the wheel again when the car picked up a puncture. Flailing tyre tread damaged the battery installation, causing an electrical fire. With hopes of a French victory dashed, the crowd was devastated.

‘Pesca’ gets airborne

1969

Having missed the 1969 test weekend in March because its new MS640 wasn’t ready in time, Matra pulled strings to get the RN138 — the famous Hunaudières straight — closed to traffic for private testing in April. Henri Pescarolo and Johnny Servoz-Gavin soon found the car to be aerodynamically unstable at high speed — and ‘Pesca’ paid dearly. The long-tail Matra took off, somersaulted into the trees and caught fire. The driver was pulled from the wreckage alive but with extensive injuries, including fractured vertebrae and burns to his arms and face. By the time the race took place, ‘Pesca’ was still in hospital but gamely commentated live for a French TV station.

The tortoise

1969

‘There’s no point in running; you just have to depart on time. The hare and the tortoise are a testimony to this.’ At the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1969, Jacky Ickx interpreted the fable The Hare and the Tortoise in his own way with one of the greatest achievements of his career and in the history of the race. Unhappy about the echelon start that had been in place since 1925, Ickx strolled — rather than ran — across the track to his Ford GT40 and drove away last. Twenty-four hours later, he took the chequered flag in first place, proving that a long-distance race isn’t won at the start but over the duration. Ickx’s personal protest spelled the end of the ‘Le Mans-style’ start, with an ’Indianapolis-style’ rolling start introduced in 1971.

Comparison with F1

1970

During the test weekend of 1971, Britain’s Jackie Oliver lapped the Le Mans circuit in his Porsche 917L faster than anyone else before him, achieving an incredible average speed of 155.626mph (250.457km/h). How that compared with a Formula 1 car of the time is an interesting possibility to contemplate — and there is a handy way to assess it. At that time, Spa-Francorchamps was a high-speed circuit of very similar length to Le Mans, the two measuring 8.762 miles (14.100km) and 8.369 miles (13.468km) respectively, so the comparison is particularly telling. There were world championship races at the Belgian track for both Formula 1 and sports cars in 1970, so let’s look at the speeds for pole position:

- Formula 1: Jackie Stewart, March, 151.638mph (244.038km/h)

- Sports cars: Pedro Rodríguez, Porsche, 160.513mph (258.321km/h)

Decisive — although there was a 3-litre limit for Formula 1 and the Porsche had a 5-litre engine. No wonder the 917 was judged ‘the greatest racing car in history’ by 50 international motorsport experts in Motor Sport magazine.

King denied access

1974

King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden is an avid sports car fan. Soon after he ascended to the throne in 1973, he was guest of honour at an official lunch at Le Mans but midway through needed to collect something from his car. On his return, without a pass, he thought that declaring his identity would suffice. The steward on the door wasn’t so sure and replied with a laugh: ‘That’s right, and I’m Joan of Arc!’ Before long, a senior ACO representative, arriving late for the occasion, was able to confirm the guest’s identity. Speaking of royal blood, special mention must go to Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg-Lorraine. Making his début at the race in 2021 with Robin Frijns and Charles Milesi in an ORECA 07, he won the LM P2 category and finished a remarkable sixth overall, behind five Hypercars.

NASCAR visitors

1976

In 1976, the ACO wanted the Le Mans 24 Hours to honour the bicentenary of the United States Declaration of Independence. What better symbol than to invite NASCAR stock cars to visit and enjoy their mighty presence with 7-litre V8s bellowing around the Sarthe circuit? Unfortunately, the Dodge Charger of Hershel McGriff and his son Doug only lasted two laps before a piston failure, but the Ford Torino of Dick Brooks, Dick Hutcherson and Marcel Mignot held out for 11 hours.

Suspicious sandwich

1979

With four Le Mans victories under his belt, Jacky Ickx was a firm favourite to win again in 1979 when Porsche made an unexpected return with a late entry of two 936/78 cars that had been mothballed after the previous year’s race. Ickx and co-driver Brian Redman had setbacks early in the race but were recovering strongly when their Porsche, with Jacky at the wheel, coasted to a standstill on the Hunaudières straight shortly before 3am. Ickx thought the problem was electrical failure but it turned out to be a broken fuel-injection drive belt. In darkness, he managed to fit the spare belt carried in the car but it quickly came loose and he got no further than Mulsanne corner. Porsche engineer Valentin Schäffer made his way out to the scene with another belt hidden in a package disguised as a sandwich. When he arrived, Schäffer found himself on the opposite side of the track from the stranded car and had to hurl the ‘sandwich’ rather obviously towards Ickx. The driver got to work again and this time managed to do a better job of fitting the belt and finally arrived in the pits, where Redman took over. Two hours later, however, they were disqualified: a marshal had spotted the delivery of the replacement drive belt and reported it.

A dozen DNFs

1986

DNF (Did Not Finish): these initials always spell disappointment for racing drivers. German driver Hans Heyer started the Le Mans 24 Hours on 12 occasions, generally with good teams and competitive cars, but never reached the finish. His attempts included three in Porsche 935s and five as a works Lancia driver, but possibly his best chance came at his final appearance, in 1986 at the wheel of a Jaguar XJR-6 shared with Brian Redman and Hurley Haywood. But it wasn’t to be: the car was lying fifth, with Heyer at the wheel, when it ran of fuel on the Hunaudières straight.

Wedding bells

1987

Masanori Sekiya has the distinction of being the first Japanese driver to win the Le Mans 24 Hours when the McLaren F1 GTR he shared in 1995 with JJ Lehto and Yannick Dalmas emerged as the unexpected winner. For Sekiya, this came after eight previous appearances in the race, seven of them in Toyotas, with best results of second in 1992 and fourth in 1993. But his love affair with Le Mans was stronger than just the race itself, for he got married during race week in 1987. His Toyota’s early retirement from the race at least allowed him to devote more of his honeymoon to his bride...

High-tech resurfacing

1988

Over the course of its history, the circuit has undergone 15 upgrades. The ninth, before the 1988 race, saw the resurfacing of the Hunaudières straight — the RN138 main road between Rouen and Tours — with the aim of making it as smooth as possible and therefore safer. The work involved the removal of 12,500 tonnes of material to flatten all significant undulations, including the easing of the ‘hump’ near the end of the straight, and laying down a new surface of high-grip asphalt. To get the best results, the civil engineers used pioneering laser technology.

Magic spray

1997

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Michel Vaillant comic strip, which was created by Jean Graton and first published in Journal de Tintin in 1957, Yves Courage entered a prototype car in 1997 called the Courage-Vaillante, with bodywork produced by Studio Graton. Starting 13th on the grid and carrying #13, the car was driven by Didier Cottaz, Jerome Policand and Marc Goossens. It settled into seventh place but as night fell it was delayed by a recalcitrant starter motor. It was the team’s physiotherapist who came up with the remedy: by applying a cold spray — the type of painkilling spray used when footballers get hurt — the starter motor miraculously worked again. Using this trick at each pitstop, the Courage finished fourth overall.

Three take-offs

1999

Mercedes-Benz had three alarming instances of its CLR cars taking off at Le Mans in 1999 despite extensive pre-race evaluation of the low-line shape’s aerodynamics. The first occurred in Thursday qualifying on the fast straight between Mulsanne and Indianapolis when Mark Webber pulled out to overtake a slower car and found the nose of his CLR lifting clear of the track. The car tipped over to one side before landing back on its wheels and slamming into the barrier. During warm-up on the morning of the race, Webber had a rather more dramatic flight in his repaired car. After cresting the ‘hump’ at the end of the Hunaudières straight, his CLR flipped end over end, landed on its roof and slid down the track to Mulsanne corner. Despite the savagery of the incident, Webber suffered only bruising, but his car was wrecked. After discussion about whether to race, Mercedes-Benz management decided to proceed after fitting its two remaining CLRs with downforce-inducing dive planes on the nose. This wasn’t enough to prevent Peter Dumbreck experiencing his own take-off for all to see on the big trackside screens. At virtually the same spot as Webber’s first accident, the car this time flew over the barriers, landing in an area that had been cleared of trees. Thankfully, Dumbreck was able to climb out of the car unaided, bruised and dazed but otherwise unharmed. With that, the team withdrew its remaining CLR.

High-speed commute

2005

Henri Pescarolo’s team hired rallying ace Sébastien Loeb for the 2005 race in its bid to beat the Audi armada. As Loeb had never taken part in the Le Mans 24 Hours, he first had to complete the standard ‘rookie’ requirement of demonstrating his competence over 10 laps of the circuit. The day of this exercise, Sunday 5 June, overlapped with the WRC Rally Turkey, in which Loeb was competing for Citroën, so a carefully planned exercise in logistics was needed. After completing the rally — he won it — he used a helicopter and private jet to get to Le Mans on time. Playstation, his sponsor, even set up a Gran Turismo 4 simulator in the aircraft so that he could practise during the journey. He didn’t finish the race that year but in 2006 he repaid Pescarolo’s faith as one of the drivers of the second-placed car.

Arriving by bicycle

2011

Marketing stunt or good team-building exercsie? It was a surprise for all onlookers at scrutineering in the Place des Jacobins in 2011 when Peugeot’s nine drivers arrived on Peugeot bicycles. Team boss Olivier Quesnel had asked his drivers — Anthony Davidson, Alex Wurz, Marc Gené, Stéphane Sarrazin, Franck Montagny, Nicolas Minassian, Sébastien Bourdais, Pedro Lamy and Simon Pagenaud — to put in some solid fitness training by cycling 80 miles (130km) from Chartres. They all looked as if they had enjoyed

the ride. Prior to this, Bob Wollek often used to ride from his home in Strasbourg to Le Mans and back again.

Miracle at Chapel

2011

In the 51st minute of the 2011 race, Allan McNish was on the attack in his Audi R18 TDI when contact with Anthony Beltoise’s much slower Ferrari 458 Italia caused the Scottish driver to lose control and skate across the run-off area. After bouncing off the guardrail, the Audi came to rest upside down in the gravel, thankfully with no harm done to the driver or anyone else. It seemed like something of a miracle at the bend called Chapel but in reality it was another piece of proof that racing cars of the modern era are exceptionally strong. Several hours later that was emphasised when another big accident befell an Audi after a high-speed brush with a slower Ferrari, this time when Mike Rockenfeller crashed heavily after Rob Kauffman strayed into his path on the fast straight from Mulsanne to Indianapolis.

Precocious youth

2014

In 2022, American Josh Pierson became the youngest driver to race at Le Mans, aged just 16 years 119 days — too young even for a normal driving licence. Sharing an ORECA 07 with Alex Lynn and Oliver Jarvis, he finished tenth overall and sixth in the LM P2 class. Prior to this, the record had been held by another American, Matthew McMurry, driving an LM P2 Zytek in 2014 when aged 16 years 202 days. To find the previous record, we have to go all the way back to 1959, when Mexican Ricardo Rodríguez made his début driving an OSCA aged 17 years 126 days, having been refused an entry the previous year because of his age. On his second visit, in 1960 aged 18 years 133 days, Rodríguez finished second at the wheel of a Ferrari Testa Rossa, making him the youngest-ever podium finisher at Le Mans.

Inseparable drivers

2018

There are some birds, most notably the parrots commonly known as lovebirds, that are called ‘inseparables’ because they pair for life and, it’s commonly believed, pine away when a partner dies. At the Le Mans 24 Hours, one could go on a flight of fancy and consider American entrepreneur Tracy Krohn and Swedish racer Nic Jönsson as ‘inseparable’ because no one else has competed together more often than these guys. From 2006 to 2018, they raced together at Le Mans 13 times in a row, with three podium finishes in their class. Their run ended when Krohn had to miss the 2019 race after crashing heavily in practice.

• The drivers: the greats, topped by nine-time winner Tom Kristensen; the rookie winners; pioneering women drivers; tales of exceptional personal endeavour and adversity.

• The manufacturers: Bentley, Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Ferrari, Jaguar, Ford, Porsche, Matra, Peugeot, Audi and Toyota have been the predominant names over the 100 years and all get their share of attention.

• The cars: the famous winners, from 1923 3-litre Chenard & Walcker to 2023 Ferrari 499P Hypercar, are featured, plus the eccentric machinery that has added fascination over the years.

• The technology: aerodynamic advances and speed landmarks; pioneering engines, including turbine, rotary, diesel, electric and hybrid; tyre and safety developments, and more.

• Numerous other themes: records, trophies, regulations, circuit changes, safety improvements, race organisation, art cars, spectating, atmosphere and curiosities.

Format: 300x260mm

Hardback

Page extent: 336

Illustration: 600 photographs & diagrams

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.