Aston Martin

The entire story

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

An extract from the chapter covering the Aston Martin DB4

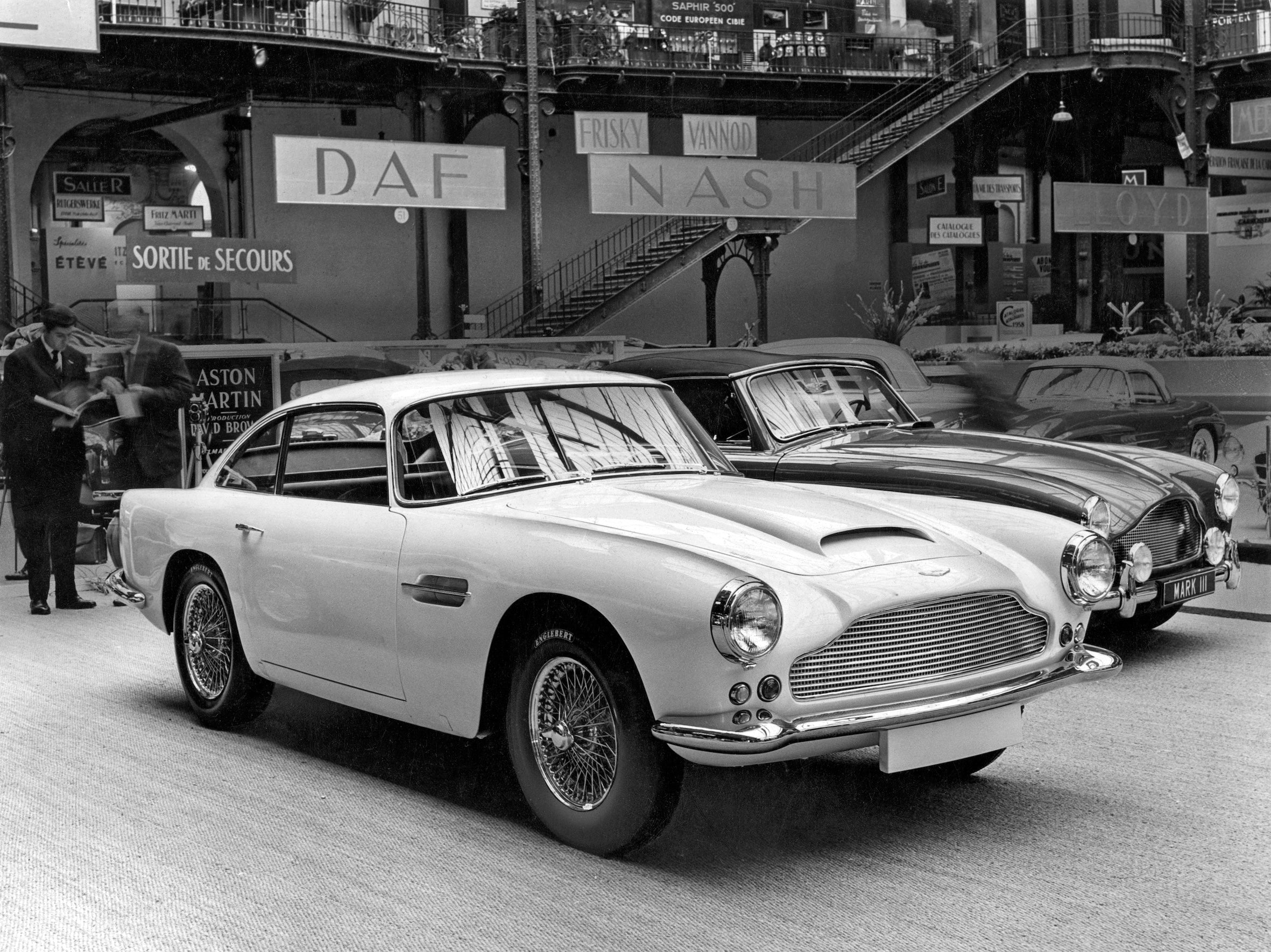

The 1958 Aston Martin DB4 was the first all-new car under David Brown’s ownership, sharing only a few components with the outgoing DB Mark III. It was a game-changer which would decisively reposition the small firm as competing against Ferrari rather than Jaguar.

The planned successor to the DB2 and its derivatives was designated DP114. Work began in 1952, although not with any great speed given the racing programme was ever-expanding and a successor was required for the Lagonda 2.6.

Harold Beach designed the new chassis for the DP114 which came well ahead of the new engine. Naturally the chassis followed the philosophy of the DB2 with a tubular perimeter frame (longitudinal side members with transverse beams). Reports produced by Paul Jackman, who was in charge of the Experimental department at the time, first noted work on the prototype chassis taking place in June 1954 when comparisons were made between the torsional stiffness of round vs square tubing. Round (lighter) tubing was used on the DB3S and square on the production DB2-4.

‘Quite frankly, prior to John Wyer taking over as general manager, I don’t think anybody knew what they were doing,’ Beach recalled. ‘The DB2 was there and people were thinking about what they were going to do next. I’d started to work on Project 114, the possible successor to the [DB2-4] Mk II; the first thing I did was to design the front suspension. I then designed a perimeter frame for this car – in those days everybody was in the separate body and chassis era – nobody thought of combining the two.’

By May 1955 a chassis had been built and the front crossmember had been designed to take wishbone front suspension – a major change from the previous trailing link and torsion bar. Reports were now referring to the DP114 as the ‘DB4’. At the rear a de Dion axle was fitted which had been proven on the DB3 and DB3S. As well as offering an improved ride, the unsprung weight was said to be 15 per cent lower than the live axle of the DB2-4.

Two months later, on taking up his post as technical director, John Wyer’s first assignment was to prepare a draft specification for a car, or rather a range of cars, to replace the DB2 series and the Lagondas. The engine specification for the DP114 now received serious consideration. Both road and racing cars would need to share a common engine, as before, and this would be the first all-new Aston Martin engine under David Brown’s ownership (the Claude Hill pushrod 2-litre and Lagonda LB6 having been inherited designs).

The company had become certain that the basic capacity for its sports car engines should be 3 litres – even before the FIA imposed its 3-litre limit in 1957 – and that the in-line six-cylinder was the configuration it was most comfortable with. The new engine would need to be capable of being enlarged to power the heavier Lagonda and to couple with an automatic transmission which the range had sorely lacked.

Wyer asked for a production engine of 3 to 3.2 litres which could be stretched to 3.6 or 3.7 litres. The cylinder dimensions of the basic design (DP186) would be a 92mm x 75mm bore and stroke giving 2,992c, while the Lagonda version was a square 92mm x 92mm to give 3,670cc. According to Wyer’s account, written in the late 1950s, Tadek Marek’s design started on the drawing board in the first week in August 1955. The LB6 3-litre had only been on the market for two years, so work on the 3.7 version started first. Simultaneously, Marek was working on the final development of the LB6, the DBA (see Chapter 4).

Wyer recalled that: ‘In retrospect, our thinking was based on a false premise. The [physical] size of engine is dictated, not by the bore and stroke, but by the size of the bearings, which governs the length of the crankshaft and thus the overall dimensions of the engine. Because Marek is an extremely good designer, he very correctly made the bearings adequate for the larger version; because he is also somewhat cautious, he made them generous, for which I am profoundly grateful.’ Before it saw use in the DB4, the 3.7-litre racing version of the engine saw use in the DBR3 and was then further enlarged to 3.9 and 4.2 litres for the DBR2 (see Chapter 5). The seven-bearing crankshaft used contributed to durability in long-distance racing events such as Le Mans.

An aluminium cylinder head had previously been developed for the DB3S but the DP186 engine rapidly gained an aluminium cylinder block – highly unusual for any British make of car at the time. According to Wyer, at the 1955 London Motor Show he and Marek showed their drawings to the Midland Motor Cylinder Company with a view to the firm taking on casting of the cylinder block. The pair were told the company had no spare capacity in its iron foundry for at least 18 months. Wyer recalled: ‘We pleaded in vain but they did make the suggestion that Marek redesigned the cylinder block in aluminium and that we took it to their associate company, Birmingham Aluminium, who had surplus capacity and were looking for work. So that is what we did and we had an aluminium cylinder block almost by accident.’

This immediately resulted in a higher cost for the future DB4, but it was thought this would easily be borne by the Aston Martin customer. In a comparison published in the 1960s, the complete weight (with starter, dynamo, clutch, exhaust manifolds and two gallons of oil in the sump) of the DBA six-cylinder used in the DB Mark III, with cast-iron block and head, was 614lb (278kg), compared to the all-aluminium DB4 engine’s 566lb (256kg). The cost of the DBA was around £26 at the time, a DB4 engine around £48.

The aluminium crankcase and cylinder block were combined for stiffness. In its production form the new engine continued the sophisticated features of the Lagonda LB6. Twin overhead camshafts operated the valves which were inclined at 80°. The camshafts were chain-driven and an auxiliary chain (with hydraulic tensioner) drove the oil pump. As with the previous engine, cast-iron wet cylinder liners were used. In road-going form the engine had a wet sump.

By February 1956 the chassis frame had been built into what the report referred to as ‘the first Prototype M Wheelbase DB4’. ‘M’ appears to have indicated medium wheelbase. A longer version may have been produced for a Lagonda.

By May 1956 a makeshift body had allowed the chassis to cover 30 miles (48km) on the MIRA test track, and by the end of the month the car had covered 7,800 miles (12,553km), including the cobbles of the pavé section, followed by speed testing at Chalgrove airfield in Oxfordshire. Several problems were found but all ‘relatively minor and readily corrected’.

Around this time a second chassis was built (later known as DP114/2) in order to accept real bodywork. The first chassis was scrapped and the engine – a prototype of the DBA unit – was transferred over, along with the suspension.

The first production DBA engine (DP164, still at the time referred to as the ‘DB4’ engine) had been completed by the end of 1955 and was being tested in ‘the prototype DB4’ in the middle of 1956. The new rolling chassis had several improvements over the first, such as a twin-plate clutch and rubber steering-

rack mountings.

Feltham to Milan

A two-door saloon body styled by Frank Feeley was mounted on the new DP114 chassis (DP114/2) in the middle of 1956. The styling had been a collaborative effort between Feeley and David Brown, based on discussions around a clay model. Wider than the DB2 series, the rear styling resembled Feeley’s earlier ‘blue monster’ Lagonda convertible prototype (see Chapter 4). According to Harold Beach, David Brown suddenly decreed that the car was 2in too high, so had the whole top section from the waist up reduced in depth by 2in, resulting in

shallower windows.

The DP114 was about to become redundant. Since late 1955 John Wyer had been looking to Italian coachbuilders to assist with the body design of the new Aston Martin, ‘feeling that we had something to learn, both in styling and, even more, in methods of construction, from the Italian school.’ It was a trend which mass-market British manufacturers BMC and Standard-Triumph followed later in the decade.

Designers such as Ghia, Vignale and Pinin Farina had extended their reach beyond their home market and were eager for new customers. The original intention was to mount the Italian body on the DP114’s perimeter chassis with the new DB4 engine.

John Wyer’s first approach had been to Pinin Farina but the company preferred working in steel rather than Aston’s aluminium, which was not negotiable for Wyer: ‘In the interests of performance, and therefore weight, the body panels must be aluminium,’ he wrote. ‘To provide the necessary rigidity the aluminium panels must be mounted on a steel framework. The acknowledged experts in this form of strong and very light construction were Superleggera Touring. Towards the end of 1955 I bought myself a ticket to Milano.’

Touring’s first Aston Martin-related work had been a two-seater spyder body style created in November 1955 by Touring’s chief designer Federico Formenti. Three spyders were built during 1956 on a DB2-4 Mk II chassis with the intention that they would be the start of a series (see Chapter 4).

Wyer took the chassis drawings for the DP114 to Milan on his first visit. ‘On his return, he told me that they were not at all impressed with the chassis,’ Harold Beach wrote in 1994. ‘And while anxious to collaborate, they would have to have a platform frame designed in such a way that their method of construction could be integrated.’

Touring had convinced Wyer that the strongest and lightest option would be a platform steel chassis frame which included the front bulkhead, floorpan and wheel arches, improving the strength and stiffness of the structure without adding extra weight. With Touring’s Superleggera system, a superstructure of light-gauge, small-diameter steel tubes was welded to points from the rear valances of the platform (below bumper level), and the tops of the wheel arches on the scuttle (below the windscreen). The windscreen, rear window frames and sections for door-hinge mountings were attached to this skeleton structure, which was then covered by the body panels. It was a complete change from the largely tubular chassis of the post-war Aston Martins.

Although the production DB4 would have a wheelbase 1in shorter than the DB Mark III, at 8ft 2in, the flat steel plates of the lower body structure freed up more interior space and two rear seats could be provided – rather than the occasional places in the 2+2 Mark III – just large enough for the DB4 to be called a four-seater. There was no longer a need for a deep door sill, further improving space and access.

Beach recalled: ‘I got myself a ticket to Milan and started my long association with Carlo Felice [‘Chi Chi’] Bianchi Anderloni and Gaetano Ponzoni of Touring. The Touring workshops in Milan were very good, but mind you, it was a bit of a poky sort of building. However, they were making Alfa Romeos in fairly large quantities.’

Federico Formenti again drew up the style for the new Aston (designated DP184), and for a four-door future Lagonda version. The shape was developed using wooden models and bore a clear resemblance to the Maserati 3500 GT which Touring was due to build in 1957. Touring was also making the Alfa Romeo 1900 C Super Sprint at the time, similarly using Superleggera construction, and Beach was able to study

the structure.

In spring 1956 Harold Beach scrapped the perimeter-frame concept of the DP114 and produced a platform chassis, which he designed in six weeks to Touring’s requirements. ‘We kept the 114 front suspension and even the de Dion rear suspension on the first prototype – but that had to come off later because of excessive noise from the chassis-mounted final-drive.’ Rack-and-pinion steering gear replaced the old worm-and-roller layout.

In July 1956 Wyer was appointed general manager, and so Beach became chief engineer with overall responsibility for co-ordinating the DB4 project, and Tadek Marek was appointed chief production designer. One of the earliest references to DP184 was found in a Design Scheme book dated 10 July 1956. The hope for DP184 was that it would be lighter than the DP114, which was now referred to as a ‘2.9-litre prototype Aston Martin saloon’.

At some point in late 1956 this first platform chassis was shipped to Milan for Touring to construct the first prototype DB4 (DP184/1). The prototype 3.7-litre aluminium DB4 engine (DP186) first ran on the test bench in November 1956. The initial claimed power output was 180bhp (Marek later wrote it was 170.5bhp), which to Wyer’s surprise it achieved the first time it ran. Moves were rapidly made towards a racing version (see Chapter 5). At the time the DBA engine in the then-new 3-litre DB Mark III produced a claimed 162bhp at 5,500rpm.

Work continued on DP184, and a report dated 1 January 1957 stated that after the first 1,000 miles of testing the roadholding was considered to be good, but the car was slower than a DB2-4 because it was 290lb (131kg) heavier.

The final styling of DP184 would be a joint effort from Touring and Feltham, but Frank Feeley had left in 1956 (he is said not to have got on with Wyer, nor enjoyed travelling to Newport Pagnell) and by then the first DB4 prototype was under construction. The completed car appears to have reached England in 1957 and ran for the first time in July, registered

7 LMP.

First impressions of the DB4

Very soon John Wyer and Harold Beach took the prototype direct to David Brown’s farm for him to try. ‘It wasn’t normal to take cars out to his farm, but the DB4 was a new car in its entirety – nothing had approached it up to that point,’ said Beach. ‘DB was the first one to drive the DB4 prototype any distance. He took the wheel and we had a hilarious drive across the Chiltern Hills. There we were, going across the Chiltern Hills at considerable speed, and the car had hardly exceeded 30mph when we took it over there!’

Tadek Marek also took the prototype for a weekend but returned it with a smashed front end, though the cause remains unclear.

The prototype had covered less than 5,000 miles (8,047km) when, towards the end of August 1957, Wyer took it on an extended test, travelling to Touring in Milan with his wife Tottie through Belgium, France, Switzerland and into Italy. The trip lasted from 23 August to 2 September 1957 and covered exactly 2,000 miles (3,219km).

DP184/1 made the trip undisguised. These were the days long before ‘spy shots’ filled the pages of car magazines. The gentlemanly editors of British car magazines were trusted to keep secrets and were treated to views of experimental cars at racetrack car parks. That said, the new Aston was more visible than some. In its October 1957 edition, Motor Sport pictured 7 LMP in the car park at Spa. It is likely that this was during the three-hour race organised by the Royal Automobile Club of Belgium on 25 August, in which DBR1/1 and DBR1/2 ran, which corresponds to the start of Wyer’s outward journey. The well-informed caption stated the car was ‘used by Mr David Brown at Spa recently’ and confirmed that, ‘the very attractive Aston Martin coupé with body by Carrozzeria Touring of Milan… has wishbone and coil-spring i.f.s. and a de Dion rear-end as well as disc brakes. A truly advanced Gran Turismo car.’

On his return Wyer’s report on the findings and future actions was dated 11 September 1957 and distributed to the heads of all departments. The detailed report was subsequently published in the AMOC magazine winter 1990/91 edition: ‘Mechanically, the car performed well, and the body remained quiet and free from defect. The most serious problems encountered during the test concerned the brakes and the internal ventilation system.’

Fuel consumption for the entire test – including many long spells at 100mph – was 16.7mpg, the oil temperature ranged from a normal 70°C to a maximum 85°C, but water consumption was heavy, so the header tank needed to be enlarged.

The engine lacked torque in the middle range and at low speeds and it was ‘necessary to make abundant use of the gears to obtain any real acceleration.’ The David Brown gearbox was new at the start of the test and while it improved with use, was ‘far too heavy and generally unpleasant, and it is even difficult to move the lever across neutral’. Used in production, the Brown gearbox would continue to attract the same criticism. By 1960 experiments were being carried out with a ZF ’box.

The final-drive, also of David Brown manufacture, was deemed ‘very noisy’ and Wyer noted that future cars would be fitted with Salisbury axles. The suspension and steering were considered satisfactory and the all-disc brakes powerful and squeal-free, although they failed completely after the first 750 miles (1,200km), before reaching Basel in Switzerland. Wyer recalled: ‘After being bled, the brakes were partially restored, but failed again between Basel and Milano, and the St Gotthard pass was crossed with virtually no brakes other than the hand brake. In Milano the spring under the master cylinder valve was adjusted and the brakes were bled again by the recommended method of setting the master cylinder horizontal, and there was no further trouble.’

The worst aspect of the first prototype was that it was ‘uncomfortably warm to drive in almost all conditions.’ Some remedial steps were taken at Touring in Milan by improving the sealing of the bulkhead and grafting hot-air outlet louvres into the front wheel arches, which in their first rectangular form Harold Beach referred to as ‘letterboxes’.

Wyer concluded that: ‘While there remains a considerable amount of development work to be carried out, it is not too early to say that we have a car which can justly be described as “Grand Touring”. The overall impression at the end of this test was that the car has a magnificent performance and is full of promise.’

DB4 testing and development continues

That September Wyer expected that the test programme would occupy the first prototype for at least the next six months. Between Feltham and Newport Pagnell, development was to concentrate on three main areas.

Engine power and torque were improved using revised camshafts, inlet and exhaust manifolds and exhaust system. The engine mountings were modified to reduce vibration, and high-speed handling was improved by revising spring rates, shock absorber settings and refining the Watt’s linkage which provided transverse location for the de Dion rear axle.

Engine development took place on the bench, supported by testing on public roads and at MIRA, and of course a great deal of development work carried out during the company’s racing programme in 1957 and 1958, albeit in dry-sump racing form. Wyer recorded that some of the road testing was at speeds of up to 140mph (this before British motorways opened). The suspension testing was carried out entirely on the road, which Wyer considered more relevant, rejecting the sophisticated chassis test rig at the BP Research Laboratories at Sunbury, as it would have been unsafe above 100mph.

Touring now built a second prototype, DP184/2, which was to have a larger fuel tank to give the 255-mile (410km) range considered appropriate for a Grand Tourer. The final capacity was 19 gallons (86 litres), including a 3-gallon (13.6-litre) reserve. The tank was situated upright behind the rear seat bulkhead, instead of under the boot floor, and the spare wheel was relocated in a recess in the boot floor. There were fuel fillers on both sides of the car, the flaps released from the cockpit as on the DB Mark III. On this second prototype, the intersection of the roof with the boot lid was moved back 7in, which raised the trailing edge of the back window by 2.6in and gave a small increase in rear-seat headroom.

While the DB4 was described as all-new, the car featured some judicious carry-over from previous models. The prototype and early production DB4s used the same ‘cathedral’ rear lights as the DB Mark III. Further modifications made on the second prototype included better wind and rain sealing of the (frameless) doors, plus an improved window winding mechanism also from the DB Mark III, which would also supply the instrument panel and door locks. Internal ventilation could be tested to some extent over the winter of 1957/58, and Wyer considered it probable that one of the cars would be sent abroad again.

Meanwhile the DP114/2 prototype – nicknamed the Walls Ice Cream van because it had been painted blue and white – became the personal car of David Brown’s wife Marjorie in August 1957. It survives today fully restored.

• Beginnings, 1913–26: Robert Bamford and Lionel Martin started producing small sporting cars that showed prowess in racing.

• The Bertelli and Sutherland eras, 1926–39: Under the leadership of Augustus ‘Bert’ Bertelli and then investor Gordon Sutherland, Aston Martins became rakish road cars bred through racing endeavour, notably at Le Mans.

• The early David Brown cars, 1948–59: A glorious period unfolded under tractor magnate David Brown, with the fine DB2 family of road cars and a serious racing programme that culminated in victory at Le Mans in 1959, plus Lagondas.

• The new six-cylinder cars, 1958–69: The superb DB4 was followed by the DB5, which shot the company’s image into orbit thanks to James Bond in Goldfinger, then DB6 and DBS completed the line.

• A family tree of V8s, 1969–2000: Despite numerous ups and downs, Aston Martin’s big hand-built V8 engine powered an enduring family of super-exclusive cars with evocative names like Vantage, Volante and Zagato, plus the ‘wedge’ Lagonda.

• Into the big time with Ford, 1987–2007: The all-new and very successful DB7 began a revival, leading to a new V12 engine, the mighty Vanquish and then the ‘VH’ cars including the DB9, V8 Vantage, Rapide and many specials.

• A successful return to racing with the DBR9 and the Vantage GTE is given a dedicated chapter.

• The rollercoaster continues, 2007 to date: From purchase by a consortium led by Prodrive boss David Richards to Canadian billionaire Lawrence Stroll’s present-day stewardship, Aston Martin’s activities have been enormously varied, even embracing an SUV (the luxury DBX) and a Formula 1 programme.

• Full specifications are included and appendices cover the James Bond Astons and ‘continuation’ cars.

Format: 272 x 223mm

Two hardback volumes in a slipcase

Page extent: 704 pages total

Illustration: 600 photographs, including colour

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.